(Missouri Independent) – In the last week of April, the Linn County Health Department signaled that the COVID-19 pandemic had cooled enough that it could discontinue weekly reports on new cases.

With only three active cases on April 21, the urgency for frequent updates seemed to have passed.

But the coronavirus came roaring back this month, with Mother’s Day gatherings, graduations, and senior class trips all contributing to its spread, health Administrator Krista Neblock told The Independent this week.

Since April 30, the North Missouri county has tallied 180 cases. That is 1.5 percent of the county’s 11,920 residents.

Most concerning, Neblock said, is that many of the cases are in young adults and children.

“With graduation, we had schools that took senior trips and had students all on buses together for 4 to 6 hours,” she said. “The kids were developing symptoms and continuing with festivities. And they only got tested on a Monday, after they had gone around and infected a significant number of people.”

Just to the west, in Livingston County, the situation is worse. The 240 cases recorded so far in May are 1.6 percent of the county’s 15,227 residents.

“Our active number is the highest it has ever been since the beginning of the pandemic,” the Livingston County Health Center said in a May 20 Facebook post.

That post left many people puzzled, said Sherry Weldon, county health administrator. The infection rate this month in Livingston County is as much as 10 times that reported for any adjoining county except Linn.

“What is concerning to me is people say why and my first comment or thought is, you wouldn’t be having this problem if you had gotten a shot,” Weldon said. “I don’t say that out loud very often.”

COVID-19 cases in Missouri, and nationally, have declined substantially since vaccine distribution began late last year. From almost a peak of 4,900 cases per day in the week before Thanksgiving, the seven-day average of the cases reported daily by the state health department fell to 459 per day as of Friday morning.

About 41.5 percent of Missourians have had at least one dose of vaccine.

Neither Linn nor Livingston counties are laggards, relative to the rest of the state, in the number of vaccines administered. They are 21st and 22nd, respectively, among 117 local health jurisdictions, with one-third of their residents receiving at least one shot.

That makes the spikes in those counties concerning for what it portends, said Dr. William Powderly of the Washington University College of Medicine.

“What we are going to see, increasingly across the country, and in Missouri, is that vaccination will lead to the situation where we have two populations — one where people are very unlikely to develop COVID and those who are still vulnerable,” Powderly said. “The CDC in its recent guidelines was very careful to distinguish between recommendations for vaccinated people and recommendations for unvaccinated people.”

The difficulty for public health officials, Weldon said, is that resistance to masks, accompanied by the May 16 guidance that fully vaccinated people could ditch their masks in most situations, means almost no one is wearing them.

“I just cringe,” she said, “when I see baseball games and basketball games in cities and nobody is wearing a mask.”

Summer surge?

Memorial Day 2020 drew international attention to Missouri as partiers bursting out from stay-at-home orders packed Lake of the Ozarks bars in a manner unseen since the pandemic arrived in March.

By that date, the worst, it seemed, had passed the state by. While major East Coast cities suffered, Missouri averaged less than 1 percent of cases nationally. At the end of May 2020, there had been 13,202 cases in the state, mainly in the two large metropolitan areas of St. Louis and Kansas City.

There were 10 counties with no cases at all. Hospitalizations, which peaked at 984 on May 5, had been reduced by almost 45 percent.

What was unknowable at the time was that cases, rising slightly toward the end of the month, would accelerate rapidly during the summer.

The state health department was reporting, on average, 172 cases per day in the last week of May 2020. It was 382 in the last week of June. The rate of new cases quadrupled to 1,502 per day by the end of July.

Most venues for large gatherings were not open in the summer of 2020.

This year on Memorial Day, few restrictions remain. The daily average of reported cases is about the same in early July 2020.

By almost every measure, the spread of the infection has now slowed and the impact on health care providers has eased. The positive rate on tests is below 4 percent and hospitalizations are less than 25 percent of their December peak.

The most recent weekly Missouri Profile Report, issued by the White House COVID task force, puts the state in the “moderate transmission” category for the first time.

A separate report, the daily Community Profile Report, spotlights Linn and Livingston counties as among eight in the nation with “rapidly rising” infections.

And as the summer starts, most restaurants are open and filling as many tables as possible. Stickers showing appropriate social distancing spots have been removed from the floors of retail stores.

Nearly every local restriction put in place to combat the virus’s spread has been lifted.

And on June 14, Busch Stadium will open to full capacity of 45,538 for the first time this year. If that day follows the pattern visible on television with current reduced crowds, few will wear masks.

“People have interpreted the drop in the numbers as a victory, that we have won the war against COVID,” said Powderly, the director of Washington University’s Institute for Public Health and co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases.

CDC guidelines state unvaccinated people can be outdoors without a mask, when they are alone, with members of their own household, or in a small group where everyone else is vaccinated.

The least safe outdoor activity for unvaccinated people is being in a packed crowd. A packed stadium on a humid, still day isn’t the same as being outdoors, Powderly said.

“This virus is still there, it can still infect people and it doesn’t care about man-made rules,” Powderly said.

The virus spreads most freely in indoor spaces that are crowded and poorly ventilated. Late spring weather will encourage people to get out, Powderly said, but the summer heat of July and August will drive many indoors to air conditioning.

If there is a surge, Powderly expects it then.

Powderly is leading a study funded by the National Institutes of Health on treatments for hospitalized patients with severe COVID. Of the more than 1,000 enrolled, a majority are under 60 years old.

For younger people, he said, “your risk is lower but it is not zero. And you still have a substantial risk of having a severe infection. It is really important that people don’t assume if you are younger you will have a mild infection so you don’t have to worry about it.”

Neighbors wary

There are two other counties, also in north Missouri, reporting cases to the state health department in numbers that equal or exceed the spike in Linn and Livingston counties.

But those reports are an example of how the general decline in cases is helping public health agencies catch up on their workload.

Health departments in Putnam County, with 4,696 people on the Iowa border, and Shelby County, with 5,930 people in northeast Missouri are entering cases, some from 2020, into the state database for the first time.

At the peak of the pandemic, data entry was put aside to focus on contact tracing and case investigation, the Putnam County Health Department stated in a Thursday Facebook post.

The county reported 479 cases in February. The state’s report showed only 385 as of Thursday, with 86 added this month.

“It’s not showing that they’re historical. So we actually don’t have a jump in cases,” Joetta Hunt, the administrator for the Putnam County Health Department, told The Independent.

In Shelby County, a similar spike has been seen in state data as a result of inputting antigen tests, said Audrey Gough, administrator of the Shelby County Health Department.

Shelby County showed 650 cases in early March, and the state report shows 657 as of Thursday.

Of the 80 new cases, state data shows the county added this month, Gough estimates that fewer than 10 have been new cases.

The surge in Linn and Livingston counties is a concern across north Missouri, said Mason Alley, a multi-county emergency planner based out of the Knox County Health Department.

“There’s always that concern that underlies — that one case may turn into 10 to 100 to 1,000,” Alley said, noting that the northeast region has been effective at communicating between counties to ensure an outbreak’s spread is monitored.

“This is essentially a neighbor who also is a rural community with a lower population density,” Alley said. “So, I mean, if it happened there, it could happen here.”

Vaccine stall

At one point, Shelby County was one of the counties leading the state in terms of the percentage of residents receiving at least their first vaccine dose. As of Wednesday, the county ranked 16th, with about 34 percent of residents initiating vaccination, according to state data.

But as it has statewide, vaccine uptake has slowed. Gough is directing residents to a nearby pharmacy because so few people are interested it doesn’t justify placing an order for hundreds of doses that will go unused for weeks.

The biggest issue health officials face is vaccine reluctance.

About half of the U.S. population has had at least one shot and 40 percent are fully vaccinated. Only Boone County in Missouri is close to that rate, with 47.9 percent initiating vaccination – the state rate is 41.4 percent – and 40.8 percent fully vaccinated, compared to 31.3 percent statewide.

On April 9, vaccinations for COVID-19 peaked in Missouri, with 82,659 shots administered. The seven-day average of shots administered peaked two days later at just under 55,000 per day.

Currently, the average is about one-quarter of that peak. Only 13,393 shots were administered on Monday.

The relatively high vaccination rates in Shelby, Linn, and Livingston counties are due to the early response from older and medically at-risk populations, health officials said.

“I would say the majority are 65 and older that we got a good response from and we honed in on them and made sure it is available here,” Weldon said.

Beyond that group, even convincing health care workers to be vaccinated has been difficult, she said.

“When people say their doctor didn’t take it, they say why should I?” she said. “My fear, of course, is they think it doesn’t work.”

In Linn County, a locally owned pharmacy has 1,000 vaccine doses on hand and Walmart has doses from a federal allotment. Neblock has used her department’s Facebook page to stress the importance of vaccines as protection for everyone.

She’s constantly battling disinformation.

“I have people who have legitimately asked me which vaccine put the tracker in their body,” Neblock said.

With few people getting shots, officials are increasing testing and case investigation to control the spread. Both Linn and Livingston counties have been contacted by the state health department with offers of assistance.

Neblock said she declined assistance.

Weldon said that the testing offered was for what are called PCR tests, which require lab processing and return results in 24 hours or longer.

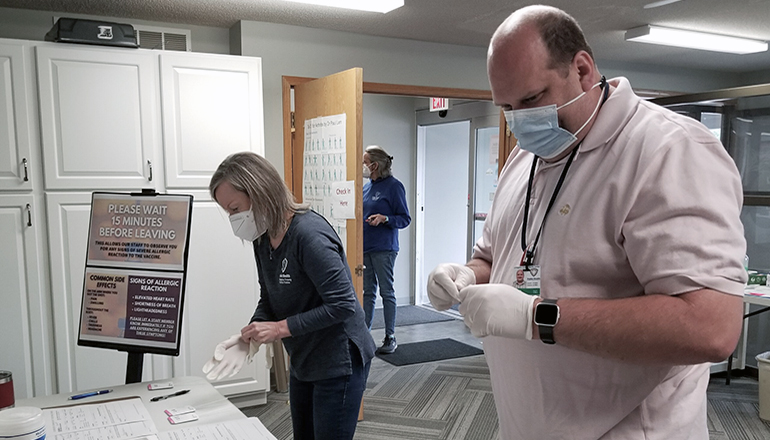

She turned that down and instead organized a drive-up antigen testing event Friday at the health department offices in Chillicothe.

The smaller counties in Missouri rely much more heavily on the rapid antigen test, which returns results in 15 minutes.

“Up here in these smaller communities where we don’t quite have as large of access to larger healthcare systems, or again, as much access in general to testing opportunities, antigen testing has been very popular,” Alley said.

Once a person feels sick and seeks a test, it is likely they have infected others. The more the virus spreads, Powderly said, the more chances it has to mutate.

“The virus is evolving to make it more infectious for humans,” he said.

And from what Weldon’s observed, that’s what is happening in Livingston County. Infections, she said, are behaving differently than past cases.

There have been a handful of what are called “breakthrough cases” in both Linn and Livingston counties. Those are cases where a vaccinated person gets sick. All the cases have had mild symptoms.

Instead of one person in a household getting sick and children remaining negative, she said, it is a full household.

“There are lots more infants and kids than we had during the school year,” she said.

As vaccinations wane, restrictions are rolled back and residents become laxer, Gough said additional spikes in cases are bound to occur.

“Everything’s wide open now.”

(Tessa Weinberg of the Missouri Independent also contributed to this article)